Policymakers to the rescue?

Slow global growth is not new to anyone who has been paying attention for the past 10 years. Policymakers have typically responded by lighting a fire under the economy: lower interest rates, lower reserve requirements for banks and greater liquidity through quantitative easing and other unconventional programs.

The trouble is, to one degree or another, major central banks face constraints to maintaining or reintroducing easy monetary policies. The U.S. Federal Reserve (Fed) risks its credibility lest it be seen as too responsive to markets and political pressure. The European Central Bank will welcome a new president later this year, making it hard for the current regime to use forward guidance to communicate its policy intentions. The Bank of England may have its hands full with the outcome of Brexit, depending on how messy things get in October. And China risks inviting a run on its currency, depending on which of the many available avenues for easing it chooses.

In short, while policymakers are unlikely to run out of ideas or ammunition to combat slower global growth, they may find themselves low on credibility, which threatens to substantially reduce their efficacy.

We expect trade wars and tariffs will negatively impact growth, but won’t cause a recession.

And now the good news

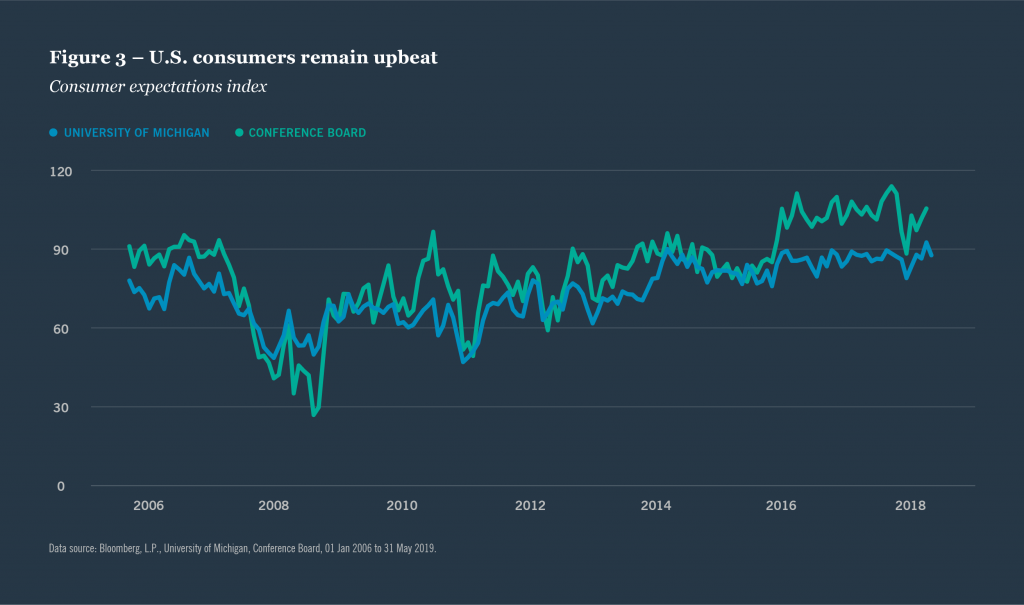

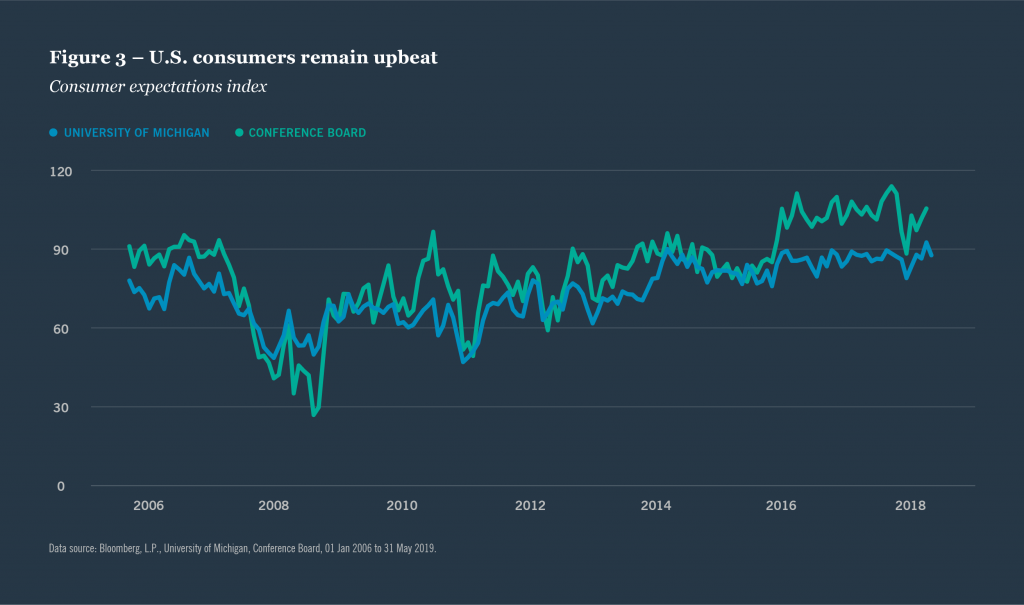

Descending from a summit can be just as treacherous as climbing up, but luckily we see a few solid footholds for the global economy over the next six to 18 months: Global consumers remain an important bright spot. Unemployment rates in most major economies are still quite low, and real wage growth has accelerated thanks to the lower supply of available workers and decreasing rates of inflation. In the U.S., both major monthly surveys of consumer confidence show continued optimism about the individual and collective economic outlooks (Figure 3). A broader mix of leading economic indicators remains pointed in a positive direction, even if the partially inverted U.S. Treasury curve is sending recession-predictor models into a tizzy.

We also do not discount China’s political will to support growth while encouraging broader economic reforms. Policymakers have room to implement further stimulus — easing regulation, cutting taxes — in ways that do not cause global financial markets to panic like currency depreciation might. The recent drop in factory output implies that a combination of lower interest rates and more fiscal stimulus may be on its way, based on China’s past behavior.

Finally, liberalizing economic reforms like those being attempted in Brazil, Spain and India — as well as the residual impact of the tax code changes in the U.S. — continue to light the way for global growth. Of course, some major economies appear to be heading in a less liberal direction, so much so that we are devoting our next section to this trend.

We think this is a good time for investors to adopt more defensive positions and seek out diversified sources of income.

Global populism and its investing implications

With Nuveen’s GIC holding its midyear meeting in the U.K., it was difficult to escape the topic of Brexit and the recent European parliamentary elections. European politics are fractured, and established political parties and politicians are losing ground to…well…something else. Just what to call that “something else” is hard to figure. Recent election results and opinion polls in developed and emerging markets countries alike seem to confirm the rise of some measure of economic populism. What, if anything, does this mean for investors and investment managers?

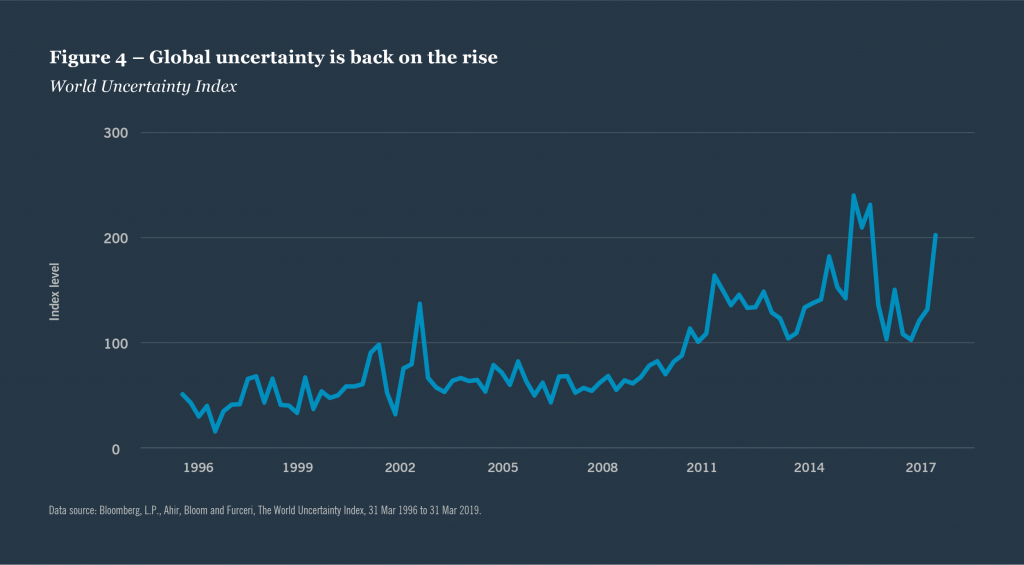

We draw a clear connection between economic populism and economic and market uncertainty. The elections of unconventional candidates or previously nonmainstream political parties often bring promises of sweeping changes to the status quo: institutions, personnel and attitudes toward markets.

The World Uncertainty Index by Ahir, Bloom and Furceri, uses data from the Economist Intelligence Unit to create a country-by-country measure of uncertainty that encompasses economic and political factors. The broad global index shows a clear, continuous rise in global uncertainty since just before the financial crisis, with a new spike in the first quarter of 2019 (Figure 4). The authors find that uncertainty today leads to higher volatility and lower output in the future. While lower output (i.e., growth) has certainly been a hallmark of the 2010s, higher volatility has not, nor have stagnant risk asset returns.

Why haven’t rising economic and political uncertainty taken a more serious toll on markets? The answer: constraints. Even the most strident or charismatic politicians may find their honeymoons cut short by outside forces. Populist economic policies often entail temporary or permanent increases in budget deficits to promote stimulative (i.e., popular) economic policies. But these outcomes can be counteracted by an independent central bank, a rating agency or a community of international investors that moves its money to a more stable destination.

Before we worry about the implications of economic populism, we must first ask whether it can prevail as a practical governing philosophy. In many, though not all, cases (think of the Brexit frustrations or the Trump administration’s difficulty appointing Federal Reserve Board Governors), the best grade we can give is an “incomplete.” As such, we will surely return to this topic in future quarters.

The right equipment for a downward climb

The world’s economy is slowing down, whether due to higher tariffs, higher interest rates or higher vote totals for populist political parties. How should investors react over the balance of 2019 and into 2020? Nuveen’s GIC proposes three clear themes for investors to keep in mind over the next several quarters:

- Keep Fed expectations in check. Markets currently believe the Fed will undertake a series of preemptive and successful interest rate cuts in the very near future. Both U.S. bond and stock markets rallied in early June, as economic data continued to disappoint to such an extent that investors saw the Fed’s intervention as inevitable. But what happens if the Fed behaves more patiently than expected or if, heaven forbid, economic conditions improve and negate the need for such action? We don’t think long periods of simultaneous rallies in stocks and bonds are sustainable. If the Fed disappoints in the next six months, we could see periods of rising interest rates and choppy or falling stock markets.

- Focus on the trade war’s real world impact. Tariffs impact companies before consumers. Consensus 2020 earnings estimates for the S&P 500 and MSCI Emerging Markets Indexes have both fallen this year, but they’ve fallen by more in emerging markets (Figure 5). Analysts are not, to our mind, accounting for the impact that higher taxes and higher wages will have on U.S. profit margins over the next several quarters. Despite the more resilient earnings outlook in the U.S. compared to other markets, U.S. stocks have grown more expensive both in absolute P/E terms and against their emerging markets peers. Tariffs are more toxic for companies’ bottom lines than for the economy as a whole. Investors would be well advised to consider that fact before rushing to buy every tariff-related dip.

- Be prepared for the base case and the worst case. Nearly every Nuveen GIC member used the word “defensive” to describe their portfolio management strategies. But being defensively invested is not the same as being uninvested. With income (interest or dividend payments) likely to be a larger percentage of total returns moving forward, investors should continue to diversify the sources of that income: corporate bonds, dividend-paying stocks and real assets have outperformed when the economy is stable but markets are jittery, as we expect them to be.